Julia Dent Grant—First Lady, world traveler, devoted partner, and quiet trailblazer—stands among the most remarkable women in American history. Yet she remains curiously absent from the nation’s collective memory, her legacy overshadowed by the monumental events and personalities of her era. A fuller understanding of her life reveals not only the depth of her influence but also a little-known historical thread connecting her final years to India—and, by extension, to the broader story of South Asia’s relationship with the United States. At 2111 Massachusetts Avenue NW, where Julia Grant spent her final years, American and South Asian histories intersect in an unexpected and meaningful way.

Born in 1826 on her family’s Missouri plantation, White Haven, Julia Dent grew up in a nation wrestling with profound contradictions. In 1848, she married Ulysses S. Grant, then a young and unproven army officer. Their marriage became one of the most steadfast partnerships in presidential history. Grant repeatedly credited Julia with bringing him the “sunshine” and emotional steadiness that sustained him through hardship, poverty, war, and the immense pressures of leadership.

During the Civil War, Julia refused the role of a distant onlooker. Instead, she traveled thousands of miles —often with their children—to remain near her husband. Her courage and constancy buoyed Grant during his most challenging campaigns. She endured the dangers of wartime travel, narrowly escaping Confederate forces on more than one occasion.

In a twist of fate, her decision not to accompany President and Mrs. Lincoln to Ford’s Theatre on April 14, 1865, may well have saved her and her husband’s lives.

A First Lady with Global Vision—and a Deep Affection for India

From 1869 to 1877, Julia Dent Grant served as First Lady with grace, confidence, and a democratic spirit that resonated with a nation struggling to heal after the Civil War. She opened the White House to Americans from all backgrounds, bringing warmth and inclusivity to a country yearning for unity. She was one of the era’s most socially engaged First Ladies, relishing the diplomatic opportunities of the role.

Her global outlook flourished after Ulysses left office. From 1877 to 1879, the Grants embarked on an unprecedented diplomatic world tour, becoming international celebrities and informal ambassadors of the United States. Their travels took them across Europe, the Middle East, and Asia.

Enchanted by India’s rich cultural tapestry, history, and color, Julia dedicated significant space in her memoirs to describing the people and traditions she encountered there. She was deeply moved by the region’s pageantry and hospitality. For Indian Americans today, her admiration for India stands as a touching reminder that long before globalization, there were Americans who embraced India with genuine curiosity and affection. Julia Dent Grant saw India not as an exotic curiosity, but as a civilization worthy of respect—a sentiment that resonates powerfully across cultural lines.

A Final Home on Embassy Row and a Legacy Secured

The final chapter of Julia’s life was shaped by both loss and profound achievement. After the Grants were ruined financially by fraudulent businessmen, Julia supported her husband during his painful battle with throat cancer. Determined to leave his family financially secure, Ulysses devoted his final months to writing his memoirs—work that Julia encouraged with steadfast devotion. Published by Mark Twain, the Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant became a literary triumph, earning Julia nearly half a million dollars and restoring her family’s fortunes. Later, Julia would break new ground as the first First Lady to publish her own memoirs, offering historians an invaluable firsthand record of nineteenth-century American political life.

Widowed in 1885, Julia moved permanently to Washington, D.C., eventually settling at 2111 Massachusetts Avenue NW. The marble-faced home she purchased had originally belonged to Senator George F. Edmunds of Vermont. The Washington Post once described Edmunds as “Honest Senator Edmunds” after he requested that the city raise his water bill, insisting that it had been calculated too low. A Post article in October 1895 celebrated Mrs. Grant’s transformation of the home into a vibrant gathering place for diplomats, military leaders, and cultural figures. Surrounded by artifacts from her world travels, she became a beloved figure in the capital’s social and diplomatic circles.

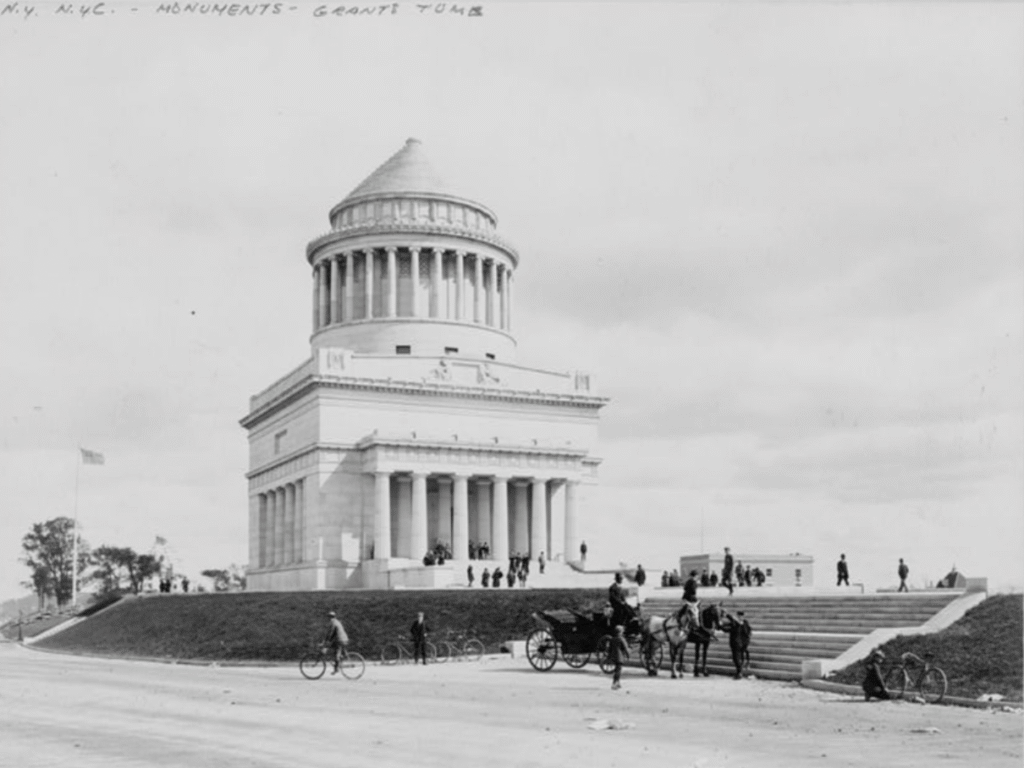

She died in 1902 and was buried beside her husband in New York.

Today, the house that once sheltered her final chapter is part of the Indian Embassy’s Chancery Complex, and the embassy’s story. This continuity of place deepens the resonance between her story and the modern Indo-American relationship, and, like other prominent figures in U.S-India relations, deserves recognition.

The Embassy already honors figures such as Jawaharlal Nehru and John F. Kennedy, whose cooperation helped shape early U.S.–India relations, and recognizing Julia Dent Grant would extend this tradition by acknowledging a woman whose life touched diplomacy, cultural exchange, and global curiosity long before such pursuits were formally recognized for First Ladies. Her admiration for India—as well as her broader engagement with cultures across South Asia—offers a natural bridge to the Indian American and South Asian American communities today, and commemorating her at this site would affirm a shared heritage of respect, openness, and historical continuity while honoring both her extraordinary life and the enduring bonds between the United States and the nations and cultures of South Asia.

To acknowledge her at 2111 Massachusetts Avenue NW would be to honor a legacy that spanned continents, connected peoples, and anticipated the global interconnectedness that defines our age.

The views presented in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent those of Diplomatica Global Media.